LONDON — In the weeks before the United States-led invasion of Iraq, as the United States and Britain pressed for a second United Nations resolution condemning Iraq, President Bush's public ultimatum to Saddam Hussein was blunt: Disarm or face war.

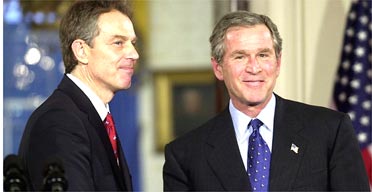

But behind closed doors, the president was certain that war was inevitable. During a private two-hour meeting in the Oval Office on Jan. 31, 2003, he made clear to Prime Minister Tony Blair of Britain that he was determined to invade Iraq without the second resolution, or even if international arms inspectors failed to find unconventional weapons, said a confidential memo about the meeting written by Mr. Blair's top foreign policy adviser and reviewed by The New York Times.

"Our diplomatic strategy had to be arranged around the military planning," David Manning, Mr. Blair's chief foreign policy adviser at the time, wrote in the memo that summarized the discussion between Mr. Bush, Mr. Blair and six of their top aides.

"The start date for the military campaign was now penciled in for 10 March," Mr. Manning wrote, paraphrasing the president. "This was when the bombing would begin."

The timetable came at an important diplomatic moment. Five days after the Bush-Blair meeting, Secretary of State Colin L. Powell was scheduled to appear before the United Nations to present the American evidence that Iraq posed a threat to world security by hiding unconventional weapons.

Although the United States and Britain aggressively sought a second United Nations resolution against Iraq — which they failed to obtain — the president said repeatedly that he did not believe he needed it for an invasion.

Stamped "extremely sensitive," the five-page memorandum, which was circulated among a handful of Mr. Blair's most senior aides, had not been made public. Several highlights were first published in January in the book "Lawless World," which was written by a British lawyer and international law professor, Philippe Sands. In early February, Channel 4 in London first broadcast several excerpts from the memo.

Since then, The New York Times has reviewed the five-page memo in its entirety. While the president's sentiments about invading Iraq were known at the time, the previously unreported material offers an unfiltered view of two leaders on the brink of war, yet supremely confident.

The memo indicates the two leaders envisioned a quick victory and a transition to a new Iraqi government that would be complicated, but manageable. Mr. Bush predicted that it was "unlikely there would be internecine warfare between the different religious and ethnic groups." Mr. Blair agreed with that assessment.

The memo also shows that the president and the prime minister acknowledged that no unconventional weapons had been found inside Iraq. Faced with the possibility of not finding any before the planned invasion, Mr. Bush talked about several ways to provoke a confrontation, including a proposal to paint a United States surveillance plane in the colors of the United Nations in hopes of drawing fire, or assassinating Mr. Hussein.

Those proposals were first reported last month in the British press, but the memo does not make clear whether they reflected Mr. Bush's extemporaneous suggestions, or were elements of the government's plan.

Consistent Remarks

Two senior British officials confirmed the authenticity of the memo, but declined to talk further about it, citing Britain's Official Secrets Act, which made it illegal to divulge classified information. But one of them said, "In all of this discussion during the run-up to the Iraq war, it is obvious that viewing a snapshot at a certain point in time gives only a partial view of the decision-making process."

On Sunday, Frederick Jones, the spokesman for the National Security Council, said the president's public comments were consistent with his private remarks made to Mr. Blair. "While the use of force was a last option, we recognized that it might be necessary and were planning accordingly," Mr. Jones said.

"The public record at the time, including numerous statements by the President, makes clear that the administration was continuing to pursue a diplomatic solution into 2003," he said. "Saddam Hussein was given every opportunity to comply, but he chose continued defiance, even after being given one final opportunity to comply or face serious consequences. Our public and private comments are fully consistent."

The January 2003 memo is the latest in a series of secret memos produced by top aides to Mr. Blair that summarize private discussions between the president and the prime minister. Another group of British memos, including the so-called Downing Street memo written in July 2002, showed that some senior British officials had been concerned that the United States was determined to invade Iraq, and that the "intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy" by the Bush administration to fit its desire to go to war.

The latest memo is striking in its characterization of frank, almost casual, conversation by Mr. Bush and Mr. Blair about the most serious subjects. At one point, the leaders swapped ideas for a postwar Iraqi government. "As for the future government of Iraq, people would find it very odd if we handed it over to another dictator," the prime minister is quoted as saying.

"Bush agreed," Mr. Manning wrote. This exchange, like most of the quotations in this article, have not been previously reported.

Mr. Bush was accompanied at the meeting by Condoleezza Rice, who was then the national security adviser; Dan Fried, a senior aide to Ms. Rice; and Andrew H. Card Jr., the White House chief of staff. Along with Mr. Manning, Mr. Blair was joined by two other senior aides: Jonathan Powell, his chief of staff, and Matthew Rycroft, a foreign policy aide and the author of the Downing Street memo.

By late January 2003, United Nations inspectors had spent six weeks in Iraq hunting for weapons under the auspices of Security Council Resolution 1441, which authorized "serious consequences" if Iraq voluntarily failed to disarm. Led by Hans Blix, the inspectors had reported little cooperation from Mr. Hussein, and no success finding any unconventional weapons.

At their meeting, Mr. Bush and Mr. Blair candidly expressed their doubts that chemical, biological or nuclear weapons would be found in Iraq in the coming weeks, the memo said. The president spoke as if an invasion was unavoidable. The two leaders discussed a timetable for the war, details of the military campaign and plans for the aftermath of the war.

Discussing Provocation

Without much elaboration, the memo also says the president raised three possible ways of provoking a confrontation. Since they were first reported last month, neither the White House nor the British government has discussed them.

"The U.S. was thinking of flying U2 reconnaissance aircraft with fighter cover over Iraq, painted in U.N. colours," the memo says, attributing the idea to Mr. Bush. "If Saddam fired on them, he would be in breach."

It also described the president as saying, "The U.S. might be able to bring out a defector who could give a public presentation about Saddam's W.M.D," referring to weapons of mass destruction.

A brief clause in the memo refers to a third possibility, mentioned by Mr. Bush, a proposal to assassinate Saddam Hussein. The memo does not indicate how Mr. Blair responded to the idea.

Mr. Sands first reported the proposals in his book, although he did not use any direct quotations from the memo. He is a professor of international law at University College of London and the founding member of the Matrix law office in London, where the prime minister's wife, Cherie Blair, is a partner.

Mr. Jones, the National Security Council spokesman, declined to discuss the proposals, saying, "We are not going to get into discussing private discussions of the two leaders."

At several points during the meeting between Mr. Bush and Mr. Blair, there was palpable tension over finding a legitimate legal trigger for going to war that would be acceptable to other nations, the memo said. The prime minister was quoted as saying it was essential for both countries to lobby for a second United Nations resolution against Iraq, because it would serve as "an insurance policy against the unexpected."

The memo said Mr. Blair told Mr. Bush, "If anything went wrong with the military campaign, or if Saddam increased the stakes by burning the oil wells, killing children or fomenting internal divisions within Iraq, a second resolution would give us international cover, especially with the Arabs."

Running Out of Time

Mr. Bush agreed that the two countries should attempt to get a second resolution, but he added that time was running out. "The U.S. would put its full weight behind efforts to get another resolution and would twist arms and even threaten," Mr. Bush was paraphrased in the memo as saying.

The document added, "But he had to say that if we ultimately failed, military action would follow anyway."

The leaders agreed that three weeks remained to obtain a second United Nations Security Council resolution before military commanders would need to begin preparing for an invasion.

Summarizing statements by the president, the memo says: "The air campaign would probably last four days, during which some 1,500 targets would be hit. Great care would be taken to avoid hitting innocent civilians. Bush thought the impact of the air onslaught would ensure the early collapse of Saddam's regime. Given this military timetable, we needed to go for a second resolution as soon as possible. This probably meant after Blix's next report to the Security Council in mid-February."

Mr. Blair was described as responding that both countries would make clear that a second resolution amounted to "Saddam's final opportunity." The memo described Mr. Blair as saying: "We had been very patient. Now we should be saying that the crisis must be resolved in weeks, not months."

It reported: "Bush agreed. He commented that he was not itching to go to war, but we could not allow Saddam to go on playing with us. At some point, probably when we had passed the second resolutions — assuming we did — we should warn Saddam that he had a week to leave. We should notify the media too. We would then have a clear field if Saddam refused to go."

Mr. Bush devoted much of the meeting to outlining the military strategy. The president, the memo says, said the planned air campaign "would destroy Saddam's command and control quickly." It also said that he expected Iraq's army to "fold very quickly." He also is reported as telling the prime minister that the Republican Guard would be "decimated by the bombing."

Despite his optimism, Mr. Bush said he was aware that "there were uncertainties and risks," the memo says, and it goes on, "As far as destroying the oil wells were concerned, the U.S. was well equipped to repair them quickly, although this would be easier in the south of Iraq than in the north."

The two men briefly discussed plans for a post-Hussein Iraqi government. "The prime minister asked about aftermath planning," the memo says. "Condi Rice said that a great deal of work was now in hand.

Referring to the Defense Department, it said: "A planning cell in D.O.D. was looking at all aspects and would deploy to Iraq to direct operations as soon as the military action was over. Bush said that a great deal of detailed planning had been done on supplying the Iraqi people with food and medicine."

Planning for After the War

The leaders then looked beyond the war, imagining the transition from Mr. Hussein's rule to a new government. Immediately after the war, a military occupation would be put in place for an unknown period of time, the president was described as saying. He spoke of the "dilemma of managing the transition to the civil administration," the memo says.

The document concludes with Mr. Manning still holding out a last-minute hope of inspectors finding weapons in Iraq, or even Mr. Hussein voluntarily leaving Iraq. But Mr. Manning wrote that he was concerned this could not be accomplished by Mr. Bush's timeline for war.

"This makes the timing very tight," he wrote. "We therefore need to stay closely alongside Blix, do all we can to help the inspectors make a significant find, and work hard on the other members of the Security Council to accept the noncooperation case so that we can secure the minimum nine votes when we need them, probably the end of February."

At a White House news conference following the closed-door session, Mr. Bush and Mr. Blair said "the crisis" had to be resolved in a timely manner. "Saddam Hussein is not disarming," the president told reporters. "He is a danger to the world. He must disarm. And that's why I have constantly said — and the prime minister has constantly said — this issue will come to a head in a matter of weeks, not months."

Despite intense lobbying by the United States and Britain, a second United Nations resolution was not obtained. The American-led military coalition invaded Iraq on March 19, 2003, nine days after the target date set by the president on that late January day at the White House.